Anaya almost stayed home from church that Sunday morning.

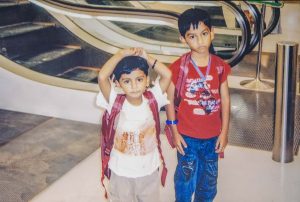

Her husband, Fahmi, a youth ministry coordinator in their province, was on the other side of the globe at a Christian youth leaders’ conference. So Anaya had to get their 11-year-old son, Ishan, and 9-year-old daughter, Naher, up and ready for the morning worship service by herself.

Naher had woken up with a fever that morning, and Anaya was hesitant to take her to church. But the children begged their mother to take them to Sunday school, even enlisting their father’s support during an early morning video chat. Anaya relented, and they headed to All Saints Church, just as they did every week.

“They were worried they would miss the Bible story,” Anaya said. “They were always curious and interested in going to church.”

Naher’s enthusiasm was no match for her fever, though, so she came to the sanctuary to rest in her mother’s lap about halfway through the morning service. The closing hymn repeated the chorus, “O Lord Jesus, we all need You.”

Anaya planned to skip the regular fellowship time after the service so she could take her sick daughter home, but she stopped briefly to talk with her sister and brother-in-law, and Ishan ran off to play with some friends.

Then Anaya’s world was shattered.

At 11:43am, two suicide bombers detonated their explosives amid the roughly 700 congregants who had gathered in the courtyard for a fellowship meal. The death toll was initially reported to be 81, including 7 children, with at least 150 more people injured. Anaya was seriously injured, while Ishan and Naher were among the seven children killed.

A Long Trip Home

Following the youth leaders’ conference, Fahmi had spent a week with some cousins in another country. A local Pakistani congregation there had asked him to speak at a youth event that Saturday, and after the event he stayed up late to talk with Anaya and the children nine time zones away via video chat.

In the middle of the night, Fahmi was roused from sleep by a phone call. His cousin, who was working a night shift, had seen footage of the Peshawar bombing on the news.

Fahmi immediately called Anaya’s phone, but there was no answer. Then he called his older brother and got no answer. He called every family member and friend he could think of, but nobody answered his calls.

“I turned on a Pakistani news channel and I saw the faces, all those faces familiar to me, who were injured,” Fahmi recalled. “It seemed I was watching all of my family on that television.”

He continued to make phone calls until he finally reached a friend from another church. “He said that it is a very, very horrible situation in my church, but he didn’t know about my family,” Fahmi said. Eventually, Fahmi reached a friend who told him that Anaya was badly hurt. He knew nothing about the children.

Within hours, friends helped Fahmi take an early flight home to Pakistan. “I was just praying to God, ‘Please don’t let anything bad have happened, that everything will be all right’,” he said. “That was my prayer in my travel. I was sensing that something had happened, but even then I was praying, ‘Please, God, let me see my family’.”

He gathered bits and pieces of information as he travelled, checking the news and continuing to call between flights. He learned that his mother, two uncles, his brother-in-law and some cousins had all been killed. In addition, his brothers, nieces and nephews, sister-in-law and many friends were injured. Then finally, he was informed that his precious children were gone.

A Place of Prayer and Peace

All Saints Church is a conspicuous and beautiful building, set inside the old city walls of Peshawar. Its ornamental crosses and Bible verses painted on the gate mark it as Christian, but the mosque-like architecture was intended to make it welcoming to Muslims, who make up approximately 98% of the Pakistani population. Painted over an arch in the front of the sanctuary are words from Isaiah 56:7, “I will make them joyful in my house of prayer.”

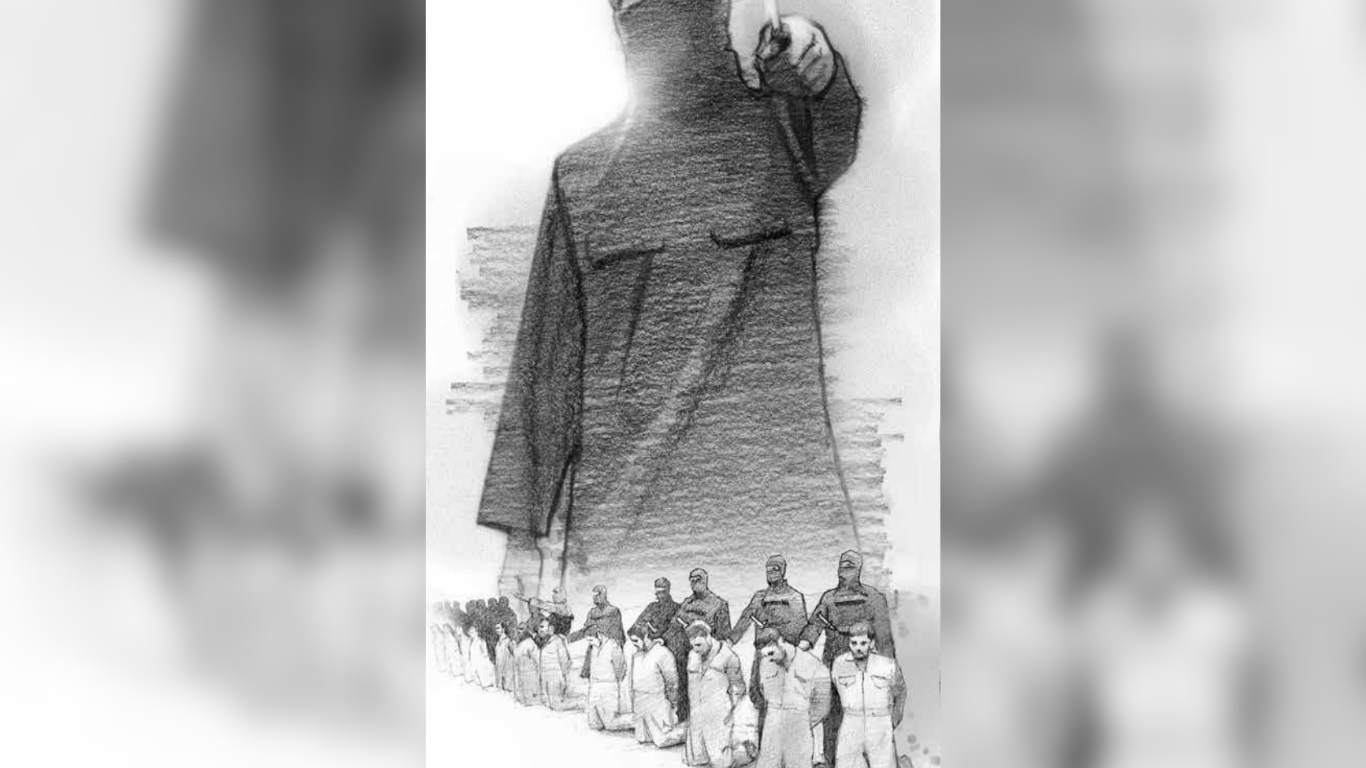

Peshawar, with a population of more than two million, is the gateway to the dangerous border frontier with Afghanistan. It is the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province, a violence-plagued area in northwestern Pakistan where bombings and assassinations are not uncommon. Its mountainous, cave-riddled terrain has made KPK the haunt of numerous Islamic terrorist groups, including al-Qaida and the Taliban. The militant group Jundallah, an offshoot of the Pakistani Taliban, claimed responsibility for the All Saints bombing.

Two Jundallah suicide bombers, each wearing six kilograms of hidden explosives packed with ball bearings and other metal pieces to cause maximum damage, slipped into the church with local workers who were delivering food for the fellowship meal. One of the men was stopped near an outside gate, but the other was nearly at the front door of the church when they detonated their explosives.

Now, more than 10 years later, the bombing remains one of the deadliest attacks committed against Christians in Pakistan. The final death toll, including victims who succumbed to their injuries weeks or even months after the bombing, was 127 people.

Through all of the suffering and grief, All Saints Church remained a light to the community. A week after the attack, the church was open and filled with worshippers, including many of the wounded and bereaved. When, near the close of the service, a car bomb was detonated in a market only blocks away, churchgoers responded in prayer rather than blind panic.

Hope After the Horror

When Fahmi arrived in Peshawar, his first stop was to see his wife at the hospital. She was in the intensive care unit, passing in and out of consciousness, her body burned and riddled with shrapnel from the bombs. Because of her fragile condition, doctors advised Fahmi to hide the truth about the children’s deaths from Anaya. So he smiled and encouraged her to focus on getting better, dodging her questions about Ishan and Naher. The visit lasted only a few minutes before nurses sent him away. Fahmi’s next stop was the morgue, to identify his children and see his mother’s body.

For Fahmi, the days that followed were a blur. “Most of the time I spent in the hospital,” he said. “My whole life was only my wife, because the kids were no more, so where else would I have been?” Between short visits with Anaya, Fahmi visited others who had survived the attack. He prayed with and comforted widows, widowers, orphans and parents who, like him, had lost family members in the blasts. He sat with the injured and provided encouragement, while privately carrying his own grief.

“I was in the denial stage for a long time, so I didn’t cry,” Fahmi said. “Friends said, ‘Why are you not crying, when you have gone through all this suffering and lost so much?’ I was just looking at God; I was praying to God, but even sometimes I didn’t know what to pray and how to pray and what to say to God.”

About 10 days after the bombing, a pastor visited All Saints and shared a message from Romans 8. “He put a question before us,” Fahmi said. “Who will separate us [from the love of God]? Will this persecution? Will something else that is this bad? I asked this question of myself while I was sitting in the church. Then I gave the same answer as St Paul did: nothing can separate us from the love of God. So that was the first motivation and strengthening of my faith.”

When Anaya was moved to a regular hospital ward, Fahmi finally told her about the deaths of Ishan and Naher. She was stunned, and then she was angry that Fahmi had kept the truth from her, angry that she had not been able to say goodbye.

Despite Anaya’s anger, Fahmi was relieved that they could finally mourn the loss of their children together. Anaya had been reading the book of Job in the weeks preceding the bombing, so those words echoed in her heart during her recovery. Just as Job was faced with accusers, some friends suggested that Fahmi and Anaya might need to repent of some secret sin, as if the loss of their two children meant they were being punished by God.

Fahmi and Anaya knew that was contrary to what Jesus taught about loss and suffering, but they were still hurt and confused as they tried to process the tragedy.

“When I was in the hospital, my faith was a little bit shaken and I was asking God why He had taken both of them,” Anaya said. “Even then I was not blaming God; I didn’t give up my faith. In all this mourning and throughout this situation, God was with us. It was God who consoled us and gave us comfort.”

Anaya began to have dreams of her children, seeing them in a place she recognised as heaven. “That also gave me some comfort that my children are in this place,” she said.

Because Anaya was not able to attend church, Fahmi arranged for family and friends to come to their home for prayer and worship services. “All the family members gathered,” Anaya recalled. “That was a time for us to cope with the suffering, and God was with us through these worship services. It helped us a lot.”

In the months following the bombing, Fahmi’s eyes were opened to a new ministry opportunity. A Korean missionary friend had begun visiting the bombing victims in their homes, and Fahmi felt led to join his friend. His presence in these visits, comforting others while going through his own suffering and grief, had a powerful effect on those he visited. He was reminded of 2 Corinthians 1:3–4, as he comforted others with the comfort he himself was receiving from the Lord.

“It gave me more encouragement when I was helping others,” Fahmi said. “It helped me overcome my own suffering, my own pain and grief.”

When she was able, Anaya joined Fahmi in these visits, especially the visits to children who had lost one or both parents in the bombing. Praying over these orphans held special meaning for them. “When we visited these children, we put our hands on their heads and told them we would be like their [spiritual] parents,” Fahmi said. “This gave them much encouragement and courage and peace and comfort.”

A few months after Anaya’s release from the hospital, two gifts from God brought the couple unexpected comfort and healing. In the new year, Anaya became pregnant with a daughter. Fahmi and Anaya also received biblical counsel in another country for their trauma and loss. For 10 weeks, they processed what had happened to their family and gained a clearer vision for serving their anguished church.

“There are a hundred families who were victimised by this bombing, but only my wife and I got this opportunity,” Fahmi recalled thinking as they considered next steps. “Now it is our time to go back and give comfort to them.”

When Fahmi and Anaya returned to Peshawar, their desire to develop a biblical counselling ministry through the church only grew stronger. They prayed that God would provide opportunities for them, and He answered their prayer. With the approval of the church leadership in Pakistan and the support of brothers and sisters in Christ, they relocated in 2015 and Fahmi began pursuing a degree in pastoral counselling.

Faith and Forgiveness

After Fahmi graduated, he received offers to serve in safer places, both in Pakistan and abroad. But the family returned to Peshawar, where Fahmi took up a teaching position at a nearby Christian seminary while initiating his counselling work.

“Here in our country there is no ‘counselling culture’,” Fahmi said. “People are suffering, but they don’t want to seek counselling.” He said people are often afraid of being judged or rejected as sinners if they open up about their pain and struggles. So instead of waiting for people to come to him, Fahmi goes to them for informal chats and prayer over tea.

“Listening is very important, so I focus more on listening,” he said. When there is a request for help or a natural opening, Fahmi then offers godly counsel and scriptural encouragement. It is a slow process, but more families are finding healing from the trauma of the 2013 attack as a result of this outreach.

Remembering how others tried to explain the deaths of Ishan and Naher as some kind of divine or karmic punishment, Fahmi works to uproot the unbiblical views that he and Anaya faced, replacing them with a biblical view. Through trauma seminars, care camps for the survivors and other teaching opportunities, Fahmi explains to participants what Scripture teaches about suffering and persecution. The result, he said, is that the church has grown stronger in faith since the attack. Fahmi and Anaya have seen God heal much of the brokenness in their lives and equip them to be instruments of restoration in their church.

That restoration has also meant coming to terms with Christ’s teachings about forgiveness.

“When the media came and asked many of the victims in our church [about forgiveness], everyone said that we had forgiven them,” Fahmi recalled. But he said they answered that way because they knew they should, not because it was really true. “This is really difficult, to forgive those who kill your children,” he said.

But time spent in solitude and contemplation, as well as his pastoral counselling studies, forced Fahmi to confront the unforgiveness in his heart. He considered Jesus’ teaching about loving one’s enemies and blessing those who persecute, and he meditated on Jesus’ act of forgiveness on the cross. Fahmi knew that forgiving the militants who committed the bombing was not only essential for his and Anaya’s healing but also a matter of faithful obedience to God.

“It was a long struggle,” he said, “but after 10 years I can say that we have really forgiven them, because our Lord Jesus forgave those who persecuted him.”

The message Fahmi clings to today, and the message he wants other Christians to learn from the bombing, is that to be a Christian is to walk by faith rather than fear. “Ten years has already passed away, and I live by faith,” he said. “Even this suffering, persecution, pain cannot separate us from the love of God. To live by faith should be our commitment to God and our way of life. Anything could happen at any time, anywhere, but if we have strong faith in God, if we believe Jesus is with us, there is no need to fear.”

Submit a Prayer