As a child, Max dreamed of following his father’s career path into the KGB (secret police) or of joining the military, both relatively prestigious professions in post-Soviet Uzbekistan. But at age 12, he learned something that changed the way he viewed his family and himself.

“I heard that I was adopted,” Max said. “My [biological] parents had left me when I was born. In our culture, it’s a huge shame. I was so sad this day. I lost my hope in the future.” Max vowed revenge against his biological parents, dreaming of finding and punishing them. He also began to pray for a way out of his hopeless life. “Every night I prayed before I slept, ‘Please let this night be my last night’,” he said. “‘Let me die in this night. I don’t want to see tomorrow, because every day for me is dark’.”

Waking up each morning with that darkness still in his heart, Max became a self-described hooligan; he got into fights, caused trouble and swore shamelessly. But he longed for something different. “I looked for peace in my heart,” he said.

In his search for peace, he became a devoted Muslim, visiting a local imam three or four times a week for lessons in Islamic prayers and Islamic history. Max had questions that his studies did not answer, however, and the imam berated him for asking them. About that time, Max learned that two of his brothers had served jail time for petty crimes, effectively shattering his dream of joining the police or military. Though he continued to pray and look for answers, his heart turned bitter towards Allah.

In early 2000, a friend Max had met at the gym encouraged him to question Islam. Tursyn, a Christian, had experienced the same pressures and poverty as 20-year-old Max, but Max could tell that something powerful had changed Tursyn’s life.

Tursyn told Max how he had come to see God in a new way and asked Max thought-provoking questions, though he didn’t initially mention Jesus Christ. Since Max’s family were among the more than 80% of Uzbeks who are Sunni Muslims, his friend’s questions about faith didn’t seem unusual. Then Tursyn said something that touched the deep longing in Max’s heart.

“Max, you know, this world has a God,” Tursyn said. “He is alive, the only one God, and He loves you.”

“I heard for the first time about God’s love,” Max recalled. “Inside, I am thinking, ‘How can a holy God love me if my biological parents left me and didn’t love me?’ Islam never talks about God’s love … That was completely new.”

The powerful message stayed with Max, and three months later he went to Tursyn again.

“Tell me about God,” Max said. Tursyn gladly told him about Jesus Christ and the salvation offered through faith in Him. Then, on 22 April — once celebrated in Uzbekistan as Lenin’s birthday — Max celebrated his own new birth.

Tursyn prayed with Max as he repented and placed his faith in Christ. “I felt that something changed immediately in my life,” Max said. “Since I heard that I was adopted, there was no peace, no night … without asking God to take my life. But this day, I slept well. This day I was so happy.”

Over time, a more profound change took place in Max’s life, beginning the next day when he read in the Bible that Jesus taught His followers to love their enemies. Max still struggled to forgive his biological parents.

“I said, ‘God, I promised from my childhood that I would punish them; after that, I will obey all of Your Word’,” Max said. But when he met his biological mother one month later, his childhood vow of vengeance yielded to the same grace and forgiveness God had shown him. “When I met with her for the first time, from her eyes I could see that she has no peace in her heart,” he said. “I understood, and I forgave her.”

At the time of Max’s conversion, the Uzbek government routinely tried to infiltrate biblical churches, hoping to gather information that would help them arrest and imprison Christians. Before being allowed to attend a church, therefore, a new Christian was often required to spend a few months being discipled by a church member to ensure that he or she was not a spy. But Max couldn’t wait to tell others how God’s grace had changed him, so he began to share the gospel before he had even started attending the only Christian fellowship in the area.

“The one thing I knew was that I got freedom,” he said. “The one thing I knew was that I met with the real living God. I shared my testimony everywhere.” But Max’s boldness soon began to attract attention, and a local imam warned his parents that they would be shunned by the community if their son continued going “the wrong way”.

While Max’s father acknowledged the positive change in his son’s life, he was concerned about the imam’s warning, a serious threat in Uzbekistan’s clan-based culture. He suggested that Max keep the life change without following Christ, but Max rejected the idea.

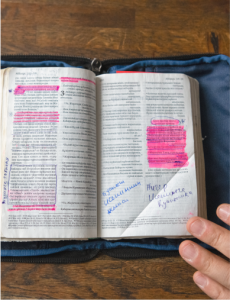

“If I take Jesus from my heart, I will become the old Max again,” he said. He struck an agreement with his father: his father would read the New Testament, and if he found anything wrong with it, Max would burn the Bible. A year later, Max’s father, mother, wife and siblings had all placed their faith in Christ.

A small number of registered Protestant churches were tolerated in Uzbekistan at the time, but biblical Christians in unregistered churches were often fined and detained for holding worship services. So when neighbours heard the unmistakable sound of worship coming from Max’s third-floor flat during a house church meeting, they reported the meeting to police.

Max was detained and interrogated for three days. Then, at a hearing weeks later, authorities fined him the equivalent of 10 months’ wages for his evangelistic work. When he failed to pay the fine, he was summoned to court to answer for the debt.

Max was sent to the office of a court enforcer named Miras, who had the power to send Max to prison or assign him to work, cleaning the city. Miras and some of his colleagues took turns bullying Max and questioning him about the faith he would not give up and the debt he could not pay.

Max remembers trembling with fear, but he said he also felt compelled to preach to his interrogators. As the men saw his boldness, he said they seemed to become embarrassed. Something about Max’s answers softened Miras’s heart; he became gentler and eventually let Max go without punishment. Upon his release, Max told Miras, “I will pray for you. God bless you. Jesus loves you.”

Between 2001 and 2007, the police, KGB and government prosecutors interrogated Max more than 50 times. He was summoned to appear in court eight times on various charges, including involvement in terrorist groups, despite clear evidence that the former hooligan had been transformed into a man of peace and joy.

Throughout those years, outreach efforts by Max and other faithful Christians produced abundant fruit. In Uzbekistan’s autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan, where Max lived, the number of underground house churches grew from one group in 2000 to ninety groups in 2007. “The persecution helped us to be strong and share the gospel,” Max said. But the explosive growth fuelled increasing government opposition.

Redemption and hope

In August 2007, Max was arrested again, and this time officials confiscated his passport and other official documents. Max’s lawyer told him that his freedom and even his life were in danger. His best chance was to go somewhere safer and hope the Uzbek government would eventually grant him amnesty.

The news broke Max’s heart. “I love Karakalpakstan,” he said. “I always said, ‘I was born here and I will die here’.” But suddenly he had to flee alone, leaving his pregnant wife and two young sons to follow later.

On 9 August 2007, in the middle of the night, a friend drove him over 1,000km to Uzbekistan’s capital, Tashkent. When they stopped to pray on the outskirts of Nukus, Max turned to take a last look at his beloved home town. He said he felt like God was telling him that he wouldn’t see the city again for a long time. “I cried all the way from Nukus to Tashkent,” he said.

Max stayed in Tashkent for a month, hoping for better news from his lawyer, but his legal situation was deteriorating. After days of fasting and prayer, Max set off on foot to cross the border into Kazakhstan. He avoided detection by disguising himself as a farmer, but he had a long way to go before reaching the relative safety of Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city.

After crossing the border, a Christian family arranged the next leg of Max’s journey — 120km to Shymkent in a shared taxi. To Max’s dismay, the other passenger was a police officer on his way to take up a new post. “I pretended to be asleep,” Max said, “but I was really praying.”

Ten minutes into the trip, the taxi came to a security checkpoint, where Max expected to be arrested if asked for his ID. He considered making a run for it, but Max knew the soldiers would shoot him before he could make it to cover. “My life is finished here,” he thought.

When the soldiers saw the other passenger’s police insignia designating his high rank, they simply waved the car through. “I wanted to hug this policeman,” Max said. “In my eyes, he was an angel from God.”

Though now an undocumented refugee, Max continued his evangelism and house church ministry after arriving in Almaty. But to his surprise and dismay, he soon ran into Miras, the court enforcer from his first arrest.

Quick to ease Max’s fears, Miras explained that he had become a Christian pastor since their encounter in Uzbekistan. “Max, you shared the gospel with me,” he said, “and it changed my heart.” Their relationship that had begun with persecution became a partnership in the gospel, as Max soon became Miras’s mentor.

When Max had been in Almaty for a few months, a friend advised him to seek official refugee status, a process that was expected to take at least 10 months. The evidence of Max’s persecution in Uzbekistan was so compelling, however, that the United Nations granted him and his family refugee status after only one month.

Since refugee status did not guarantee Max’s safety, his friends carefully guarded his whereabouts while transporting his family to join him in May 2008. They travelled under cover of night, changed cars repeatedly and took circuitous routes. But even these precautions weren’t enough. Three days after the family’s arrival, Uzbek agents and Kazakh police broke into their home and abducted Max.

“When I asked why they were arresting me, they beat me like I really was a terrorist,” Max said. “They asked me, ‘Where are your guns? What is your target?’” Max tried to show them his refugee documents, but they were not interested; the Uzbek agents intended to return Max to Uzbekistan.

Max’s wife immediately contacted international refugee organisations, which searched for Max for three days. As media attention intensified, the Kazakh government decided to release Max from the secret jail where he had been detained.

News of his abduction prompted several countries to offer Max and his family sanctuary. “A lot of people wait 10 years, and they can’t move [to these countries],” he said. “They want to go, but I wanted to stay.” Max fasted and prayed for 36 days before making a decision. “OK,” he told his family, “we will stay here. God will be with us.”

In January 2010, the Kazakh government announced that it was deporting all refugees. Those with passports fled to places like Türkiye, while those without passports, like Max, had a more uncertain future.

On 5 September, Max was arrested and notified that he had 40 days to appeal his deportation. Meanwhile, during his absence from Uzbekistan, authorities had increased his charges, claiming he was the mastermind of a terrorist cell. He was now on Uzbekistan’s “100 Most Wanted” list.

Max assumed that his deportation and ‘disappearance’ were imminent. In jail, he waited and prayed, thinking he would never see his family again. Though Max did not learn the extent of the efforts until later, political pressure from other countries, public protests, international negotiations and a worldwide prayer movement ensued on his behalf.

Faith, Freedom, and Global Ministry

Then, on 4 December, Max was released from prison and driven straight to the airport, where his family were packed and waiting for him, along with 50 Christian friends who had come to pray for them. Less than 24 hours after stepping out of jail, Max walked into a flat in Sweden that would be his family’s new home.

Having to learn a language and adapt to a different culture didn’t slow Max’s faithful ministry work. In Sweden, he found fellowship with believers from many different countries, and he and his wife continue to reach out to the multiethnic Muslim community there.

Max also joined a global Christian organisation to lead its Turko-Russian ministries, which cover 230 million people and 37 languages, including the Turkic languages Karakalpak, Kazakh and Uzbek.

When Max teaches Christians now, he prepares them for the likelihood of persecution so they can face it with hope. “Persecution is not new,” he said, “but nobody [has been able] to destroy God’s children.”

2Timothy 4:2 Preach the word! I was just reading this text when your story came to mind thank You for your Love of our Lord’s gospel it is a strength to each one prayers and Love

Praise the Lord